The hype for Longlegs has been incredible. Every few days some lucky bastard would pop up on Twitter, having just seen it, saying something along the lines of “Longlegs carved my heart out of my chest and made me EAT IT” or “Longlegs followed me home from the theater and slept on my couch and now it WON’T LEAVE”—so it’s fair to say I’ve been a little excited to see it.

My immediate response was that it wasn’t that scary, but as the hours went on I realized that wasn’t the point. What Oz Perkins and his team are after is a sense of dread that grows and grows and stays with you long after the credits. That sense of dread did, in fact, come home with me. And it has refused to leave. Longlegs isn’t interested in jump scares, though there are a couple, and it’s not about showing a ton of gore on screen, though there is some. It’s much more about how sometimes the horror takes up residence in your life an won’t leave, no matter how many rules you try to follow.

But it also made me giggle with delight! Like all great horror, comedy is only a razor’s width away, and I was pleasantly surprised by how often it leaned into moments of weird humor, or moments that felt like—certainly not parody, but moments that acknowledge horror tropes.

Longlegs was written and directed by Osgood Perkins, whose previous films include The Blackcoat’s Daughter and I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House, and his next project is an adaptation of Stephen King’s “The Monkey”, for which I am just slightly excited. Longlegs’ plot is simple, the better to let atmosphere and tone rule the day. “Longlegs” is a serial killer who’s been at work in the Pacific Northwest for 30-ish years. There are some inexplicable things about the crime scenes where he leaves his notes, and after hitting some dead ends, a young agent named Lee Harker has been assigned to the case. Maika Monroe plays Lee Harker, and there is not a single untrue second in her performance. Her boss, Agent Carter, is played by Blair Underwood who usually seems to be doing a deadpan impression of an no-nonsense, seen-it-all FBI agent from TV, which is an absolutely brilliant touch. Alicia Witt is Ruth, Lee Harker’s mother, also perfect in the role, and you can see how they fit together as mother and daughter. And this almost goes without saying, but Nicolas Cage continues being one of our most interesting actors with his turn as Longlegs.

I am trying not to say anything that will spoil this film—obviously there are already theories and interpretations all over the internet, but this movie is special, and I hope you see it with your own eyes and no one else’s. I’m going to vaguely talk about themes below, so if you want to know nothing, hop out now and come back after you’ve seen it, with my final note that if you even remotely care about horror, you need to see it.

In a similar way to Late Night with the Devil and The Black Phone, Longlegs draws on previous decades—there’s a roiling current of Satanic Panic under the plot. There is also a constant drumbeat of the vulnerability of young girls, the tissue thin veneer of the American Family. The walls and borders that we think keep us safe prove incredibly porous, and possibly nonexistent.

The thing that I really loved is that Longlegs dispenses with all the boring stuff and fake obstacles that are often in a movie like this. Sometimes to a comical degree. If someone has a hunch, it’s followed. If someone thinks there’s a clue at a years’-old crime scene, the characters drop everything and go straight there, in the middle of the night, during a thunderstorm.

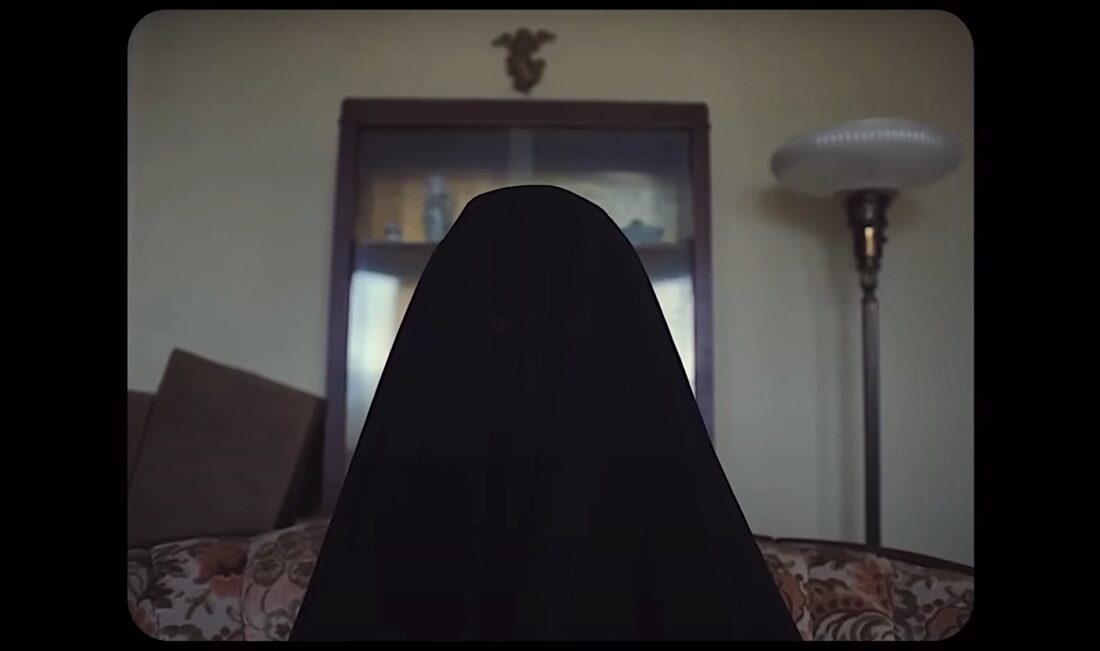

But even saying that much—none of that is what this movie’s about. What it’s about it being alone in a dark house, shadowy corners all around, and feeling a growing certainty that there is something in those corners. There can’t be. The doors are locked, the windows shut. There is no way in, you’re sure of it. And yet, you can feel breathing that is not your own.

The thing the Longlegs gets at is the undercurrent of a lot of great horror: what if the maniac is right? What happens when a person turns a corner and discovers that the rational world they thought they lived in, isn’t real? Or it’s not that it isn’t real, it’s just that it isn’t relevant anymore, because the irrational world is more powerful. The person babbling “nonsense” and doing creepy shit at the hardware store is the only one who’s tapped into the truth. He’s been right the whole time, and the world is not playing by the rules you’ve been taught it does.

To be clear, I’m not speaking in metaphors about our world—it’s quite clear to me that our world is a story we’re telling each other as we go along, and it’s up to us to decide which story is the most powerful.

Longlegs doesn’t take place in our world. Longlegs takes place in a world where evil is real, and has already largely won, because people were blind to it.

This is a movie that knows its genre. This is a movie that respects you, and trusts you to come with it. At one point, a character quotes a long passage from the Book of Revelation, and another cuts them off by saying, “Yeah, it’s the Book of Revelations”—and the first character, instantly, says “Revelation. There’s no “s”, it’s singular.”

Because this is a movie that knows that you’ve seen people quote that book many, many times, and that almost every time they said “Revelations”, and no one has corrected them. Because it’s a placeholder, in those movies. It’s standing in for “batshit religious text”—except the Book of Revelation is an actual text, written by actual people, with actual meaning to them. It was part of a specific context. And the makers of this movie know that, and they know the characters know it, and they trust you to know it, and to feel a thrill of recognition when the person insists on getting it right.

If a person is going to do research, they are by-god going to do it alone, in a dark library, under a sole reading lamp, the black night seething just past an improbable number of windows. If a person is going to have a home, it’s either going to be a totally isolated cabin in the woods, or a nice little house, halfway between suburban and rural, that is so overrun with clutter that you can barely move. If there’s going to be a doll, it’s going to be creepy. If there’s music, it’s going to be glam rock applied in unsettling ways.

Which gets to the last thing I’ll try to get at. What Perkins is doing here is creating a new icon—or, really a few of them. Longlegs is an unknowable monster. There’s no gritty origin story, we don’t hear anything about his meet-cute with Satan, we don’t know why particular dates are important—it all just IS. Longlegs’ accomplice is, in a way, a much more knowable monster. We can understand exactly why they do what they do, but most of us, hopefully, don’t know how. This is a movie where the main character seems to have only one connection, to her mother. We meet Agent Carter’s family briefly. Lee Harker never calls a friend, she never goes to brunch, there are no birthday parties in an FBI breakroom. (Though to be fair, this movie isn’t really a safe space for birthday parties.) There is work, and there is dread, and there is the dark—and the growing certainly that no amount of work will keep the dark at bay.